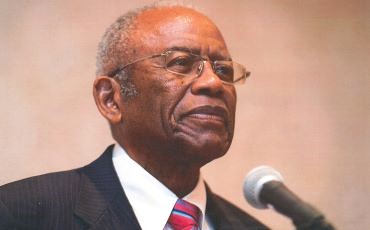

Author on Gender, Race & Ethnicity; Professor Emeritus of Legal Studies & Sociology at Kenyon College

Ric S. Sheffield Biography

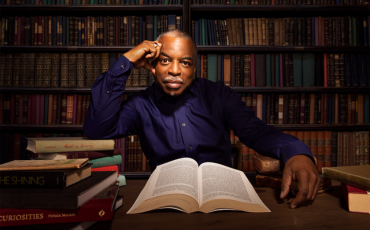

Ric S. Sheffield is Professor Emeritus of Legal Studies and Sociology at Kenyon College. He was the founding Director of the John Adams Summer Scholars Program in Socio-legal Studies and the inaugural appointee as the Peter M. Rutkoff Distinguished Teaching Professor of American Studies, Diversity & Inclusion

Before coming to Kenyon, he served for a decade as an Assistant Attorney General for the State of Ohio. He began his legal career as a civil rights lawyer handling primarily sex and racial discrimination cases. Subsequently, he held the position of chief attorney and head of the state’s consumer protection division.

In addition to research that has focused upon the relationship between law and issues of gender, race, and ethnicity, he has spent several years examining issues involving the history and experience of African Americans in rural Ohio. He is among a select group of scholars chosen to participate in the Ohio Humanities Council’s speakers’ bureau, lecturing widely on issues of race and law as well as rural diversity. He has published articles, reviews, and book chapters on topics including legal history, the legal profession, and African American social and legal history. Sheffield is the author of "We Got By: A Black Family’s Journey in the Heartland" and the forthcoming "False Promises: The Struggle for Black Voting Rights in 1800s Ohio," which examines early voting rights cases and the brave men who brought them in the state of Ohio in the mid-to-late 1800s.

He is a graduate of Case Western Reserve University where he attended college, graduate school in sociology, and law school. He has extensive administrative experience that includes serving on various statewide policy-making and regulatory boards, chairing academic departments and programs, and several years on Kenyon College’s senior staff as an associate provost. He is the founding director of the Knox County (Ohio) Black History Digital Archives, one of the first and few of its kind with a focus on rural life, and has led workshops on researching and exploring local Black history and rural diversity.

Contact a speaker booking agent to check availability on Ric S. Sheffield and other top speakers and celebrities.

Ric S. Sheffield Speaking Topics

-

Diversity in the Heartland: Exploring the Impact of Increasing Diversity on Small-town Culture

The rural Midwest region of this nation has been home to various racial and ethnic groups, albeit in small numbers, from the earliest days of settlement by non-indigenous people. This absence of a significant numerical presence resulted in the lives and experiences of these people being largely overlooked, if not outright ignored, by the mainstream press, academicians, and local historians. Even popular culture, by the absence of the depiction of rural folks of color, suggests that their presence was either non-existent or didn’t have any meaningful impact upon the region. Among the earliest migrants to the area were African Americans, both free and formerly enslaved. The migration patterns throughout the Midwest saw many, if not most, Black families head north out of southern states during Reconstruction and again after the World Wars largely to seek work in rapidly industrializing urban areas like Pittsburgh, Detroit, Chicago, and Cleveland. A much smaller proportion of the Black migrants chose to settle in rural areas where they could take up farming or engage in other types of wage labor within small-town environments with which they were familiar. European immigrants came to the rural Midwest to join family and former townsmen who had settled in these areas. Regardless of their countries of origin or the fact that many were non-English speakers, white migrants more easily integrated into the social fabric of small towns because of race. For most other nonwhite persons, there were few of the traditional draws to settle there: no specialized labor market or economic attractions; no existing ethnic or cultural enclaves; and few familial ties. As a consequence, racial and cultural differences became and have remained major factors in how communities are organized and experienced despite the fact that white residents tend not to see or even accept that to be the case. This program sheds light on these hidden “communities within.”

-

A History of Race and the Right to Vote: The Example of the Reconstruction Era Ohio Cases

The right to vote, long hailed as the embodiment, sine qua non, of liberty in American society has special historical significance for persons of African descent in the United States. While many northern newspapers were quick to condemn the recalcitrant southern states’ resistance to granting suffrage to Black men, few citizens appreciated how often African Americans suffered the same indignities in the regions north of the Mason-Dixon line. The quest for this quintessential right of citizenship was fraught with challenges and frustration, even in free states like Ohio, especially in rural communities. In weighing the often-dire consequences of resistance to attempts to vote against the potential gains thought to come from the elective franchise, Black Americans in the upper Midwest literally risked life, limb, and livelihood to claim their places at the polls.

-

How do I book Ric S. Sheffield to speak at my event?

Our experienced booking agents have successfully helped clients around the world secure speakers like Ric S. Sheffield for speaking engagements, personal appearances, product endorsements, or corporate entertainment since 2002. Click the Check Availability button above and complete the form on this page to check availability for Ric S. Sheffield, or call our office at 1.800.698.2536 to discuss your upcoming event. One of our experienced agents will be happy to help you get speaking fee information and check availability for Ric S. Sheffield or any other speaker of your choice. -

What are the speaker fees for Ric S. Sheffield

Speaking fees for Ric S. Sheffield, or any other speakers and celebrities, are determined based on a number of factors and may change without notice. The estimated fees to book Ric S. Sheffield are under $10,000 for live events and under $10,000 for virtual events. For the most current speaking fee to hire Ric S. Sheffield, click the Check Availability button above and complete the form on this page, or call our office at 1.800.698.2536 to speak directly with an experienced booking agent. -

What topics does Ric S. Sheffield speak about?

Ric S. Sheffield is a keynote speaker and industry expert whose speaking topics include Anti-Racism, Author, Black Heritage, Black History Month, Civil Rights, College, DEI, Diversity & Inclusion, Education, History, Overcoming Adversity, Political, Political Science, Social Activism, Social Justice, Social Sciences -

Where does Ric S. Sheffield travel from?

Ric S. Sheffield generally travels from San Francisco Bay Area, CA, USA, but can be booked for private corporate events, personal appearances, keynote speeches, or other performances. For more details, please contact an AAE Booking agent. -

Who is Ric S. Sheffield’s agent?

AAE Speakers Bureau has successfully booked keynote speakers like Ric S. Sheffield for clients worldwide since 2002. As a full-service speaker booking agency, we have access to virtually any speaker or celebrity in the world. Our agents are happy and able to submit an offer to the speaker or celebrity of your choice, letting you benefit from our reputation and long-standing relationships in the industry. Please click the Check Availability button above and complete the form on this page including the details of your event, or call our office at 1.800.698.2536, and one of our agents will assist you to book Ric S. Sheffield for your next private or corporate function. -

What is a full-service speaker booking agency?

AAE Speakers Bureau is a full-service speaker booking agency, meaning we can completely manage the speaker’s or celebrity’s engagement with your organization from the time of booking your speaker through the event’s completion. We provide all of the services you need to host Ric S. Sheffield or any other speaker of your choice, including offer negotiation, contractual assistance, accounting and billing, and event speaker travel and logistics services. When you book a speaker with us, we manage the process of hosting a speaker for you as an extension of your team. Our goal is to give our clients peace of mind and a best-in-class service experience when booking a speaker with us. -

Why is AAE Speakers Bureau different from other booking agencies?

If you’re looking for the best, unbiased speaker recommendations, paired with a top-notch customer service experience, you’re in the right place. At AAE Speakers Bureau, we exclusively represent the interests of our clients - professional organizations, companies, universities, and associations. We intentionally do not represent the speakers we feature or book. That is so we can present our clients with the broadest and best performing set of speaker options in the market today, and we can make these recommendations without any obligation to promote a specific speaker over another. This is why when our agents suggest a speaker for your event, you can be assured that they are of the highest quality with a history of proven success with our other clients.

Ric S. Sheffield is a keynote speaker and industry expert who speaks on a wide range of topics such as Diversity in the Heartland: Exploring the Impact of Increasing Diversity on Small-town Culture, A History of Race and the Right to Vote: The Example of the Reconstruction Era Ohio Cases, The Community Within: Discovering African American History in the Rural Midwest and Bricks & Mortar Won’t Do: Building Bridges for Rural Diversity on the Shoulders of Empathy and Compassion. The estimated speaking fee range to book Ric S. Sheffield for your event is available upon request. Ric S. Sheffield generally travels from San Francisco Bay Area, CA, USA and can be booked for (private) corporate events, personal appearances, keynote speeches, or other performances. Similar motivational celebrity speakers are Yoruba Richen, Clayborne Carson, Michael Eric Dyson, Dr. Carolyn Jefferson-Jenkins and S. Lee Merritt. Contact All American Speakers for ratings, reviews, videos and information on scheduling Ric S. Sheffield for an upcoming live or virtual event.

This website is a resource for event professionals and strives to provide the most comprehensive catalog of thought leaders and industry experts to consider for speaking engagements. A listing or profile on this website does not imply an agency affiliation or endorsement by the talent.

All American Entertainment (AAE) exclusively represents the interests of talent buyers, and does not claim to be the agency or management for any speaker or artist on this site. AAE is a talent booking agency for paid events only. We do not handle requests for donation of time or media requests for interviews, and cannot provide celebrity contact information.

If you are the talent and wish to request a profile update or removal from our online directory, please submit a profile request form.